Note

This article is a written summary of a talk I gave at BarCamp LA #4, with some bugfixes.

UPDATE 27-Jan-2014

My presentation used a bunch of graphics I swiped from Google Images, since I was in a hurry. I'd like to extend apologies/credit to my sources (or the sources for those sources). But I can't link to them because they all went missing, and I don't like getting search penalties for having my own pages in bad shape with dead links. Still, the original links were:

- highway barrier -

http://images.jupiterimages.com/common/detail/40/05/23410540.jpg - rc circuit -

http://www.physics.byu.edu/faculty/berrondo/su442/ac.pdf - resistor -

http://www.dragonmodz.net/images/resistor.gif - capacitor -

http://www.hkcapacitor.com/product/TS02_Metallized_Polyester_Film_Capacitor.gif - microcontroller -

http://www.intertexelectronics.com/images/-MC68701S.jpg - grandparents -

http://dclips.fundraw.com/zobo500dir/grampa_39_n_gramma_celso_02.jpg - moore's law -

http://www.developers.net/storyImages/062404/inteldemystifying1.jpg - hanz/franz -

http://blogimg.com/docisin/hans_franz.jpg

Virtualization is a big deal these days; it's in the news and there's a lot of activity in the stock market surrounding the phenomenon. I want to briefly talk about ways I foresee virtualization being applied that are a bit more radical than how it's generally being thought of today. In particular, I make the following claim:

Software applications are going to be increasingly built up from dozens of virtual machines per program.

To give some supporting evidence, I'll relate an analogy with how problem-solving in electronics evolved over the past few decades.

Solving a problem the EE way

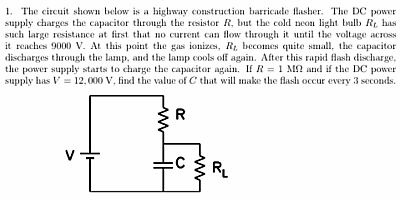

By degree, I'm an electrical engineer. And the kind of work that we used to be paid to do was that you'd have a mission like: "Make this highway construction barrier light blink every 3 seconds":

To do this, you're going to need a power source and a light. That's a given. But electrical engineers can recognize the highway-barrier task as one of those problems that can be done with just 2 additional parts--a resistor and a capacitor. In fact, it's a textbook case. So I'll show you what that kind of problem looks like:

Note

taken from http://www.physics.byu.edu/faculty/berrondo/su442/ac.pdf)

Picking a resistor R and a capacitor C can give you the desired effect of a certain brightness and a certain amount of time between blinks. But it's not like there's a specific value of C which corresponds to "3 seconds". And there's not a value of R which matches "12,000V". If you picked two components that satisfied your specification, you'd have to work the equations out again and replace both pieces if anything changed.

Solving that same problem the C.S. way

If you're familiar with computer science, and someone told you to make a light blink periodically, your mind would probably jump to something like this:

const VOLTAGE_MAX = 12000;

const BLINK_PERIOD_SECONDS = 3;

const FLASH_TIME_MILLISECONDS = 500;

const UPDATE_INTERVAL = 100;

var lamp = HighwayBarrier.getLamp(this);

forever () {

lamp.setVoltage(0);

sleep_msec(

BLINK_PERIOD_SECONDS * 1000 -

FLASH_TIME_MILLISECONDS);

lamp.setVoltage(VOLTAGE_MAX);

sleep_msec(FLASH_TIME_MILLISECONDS);

}

I'm hand-waving here to say that these are functionally equivalent. The reality is a little too tied up with light & power to make this a "good" example. But it's a simple and visceral way to see how digital signal processing (CS way) differs from analog circuit design (EE way).

Cost comparisons of the approaches

For the CS approach you'd you'd need some kind of compiler or interpreter. And you'd need a CPU to run that program. Typing "microcontroller" on Google Images I found this fellow as the first hit:

Then I looked for a price on it and got $20.61. That's a heavyweight unit for this humble task, and crazy expensive--but I'm going to run with it. By contrast, the EE way uses two parts that probably cost a few pennies. Let's estimate 10 cents for the capacitor and 10 cents for the resistor. So off the cuff we might guess that the EE way is approximately 100 times cheaper per Highway Light manufactured.

Furthermore, integrated circuits that can run arbitrary programs are not built out of 2 parts, but rather millions of individual electronic components. So we see how grotesquely wasteful the CS way is. But let's look at the big picture.

Looking at the bigger picture

It's pretty obvious how the CS code works--and I didn't even comment it. If I asked your grandparents to change it so that it would go to 13,000 volts instead of 12,000 volts... or to blink over a 10 second period instead of 3 seconds, they'd probably be able to point to the right lines. But who thinks their grandparents could make the necessary changes to the circuit?

Plus there's flexibility with the microcontroller--if you decide you want the light to ramp up and ramp down in brightness instead of blip on briefly, it's easy code to write. If you want there to be a special case where during daylight hours the lights turn off to save power, you can do that with an "if" statement. Though computer science is a deep and complex field in its own right... for things like this it takes a relatively trivial amount of education to do than analog circuit design. And modifying the program after the fact, once written by a competent programmer, can be extremely easy.

So even assuming a factor of 100 manufacturing cost difference--with an overkill microcontroller that can dance and sing (should your project ever get new requirements)--the $20 could pale in comparison to the labor charge difference.

Virtual machines are like Integrated Circuits

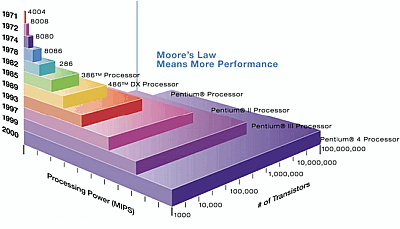

In the years during my EE degree and afterward, I watched analog circuit engineering become a niche discipline. In the meantime, the norm for hardware solutions is to use millions of electronic components to do a job that two or three well placed ones could do. This makes perfect sense--we know that a human time and ability to manage complexity doesn't scale, but Moore's Law has so far:

So now let's start thinking of microprocessors as being like virtual machines. Then the parallel to resistors, capacitors, and inductors--the building blocks of analog circuits--would be lines of code. Just how a chip with a layout of components rivaling a large city was once seen as an overkill way of making a highway light blink... there are a lot of problems today that people wouldn't even think of using a Virtual Machine for. It would be "crazy" and "wasteful".

But I'm going to tell you my bet: software applications are going to be increasingly built up out of dozens of virtual machines per program. This will be due to a similar economy of scale to what happened with integrated circuits. So here are some radical ideas about those trends.

Prediction 1: Porting and cross-platform libraries will die out

My hatred for porting comes partially from a deep-seated psychological issue of playing games like Pac-Man in the arcade as a kid, and then you'd buy the version for the Atari and it would look nothing like Pac-Man. So porting and I started out on the wrong foot, and my experiences with porting code have only reaffirmed my belief that you shouldn't do it. Here's a picture that makes me sad, a few of the first 60,000 google image hits for "Tetris Screenshot":

I really believe application developers are going to pick a platform, make their program really work on that particular platform, and ship it out to users with the expectation that they are going to run it in a virtual machine. When you run the application the details of the underlying OS will be hidden from you; it will already be configured.

I expect we'll see virtual machine versions of programs catch on and replace the idea of installing the native versions within the next couple of years. An implication here is that we'll be saying goodbye to things like the Windows and MacOS versions of the GIMP. People will learn and accept the idea that different applications have different "skins", so if the program doesn't look and act like their host OS they won't be terribly concerned.

Prediction 2: Some operating systems will just do interfaces

We're already seeing that some operating systems are succeeding based on their ability to have a nice user interface presentation. People are doing serious work on MacOS -- using it basically as a glorified terminal. I can imagine that applications of the future will have a virtual machine in them which is for an OS specifically suited to the user interface needs of the application, while that OS may not actually run any of the program's underlying logic.

In other words, rather than using a GUI library and interfacing with a client, you'll have a full blown OS whose sole purpose is to look snazzy. I think it will be a great place to see OSes that haven't been gaining traction otherwise, perhaps a resurgence of things like BeOS and OS/2.

Prediction 3: Libraries running in their own virtual machines

I've pushed the idea that many applications you install on your desktop will be running in virtual machines. That's not outlandishly far off of what's actually happening. But how about something crazier: would you ever use a string library that had its own daemons and filesystem? Perhaps even something esoteric, like QNX?

Where we once used libraries, or even a few lines of custom code...we will see a rise in the usage of whole entire operating systems. You might laugh at that, but as Hanz and Franz would say: "hear me now and believe me later".

When performance and memory usage are less of a concern than security and the leveraging of human effort--you really might want to use heavily debugged and peer-reviewed systems that are maintained by a group that has standardized on a completely different platform from your project. It will be typical, if not expected, that your project will wire together virtual machines with all the casualness that people pipe together commands in the unix toolkit paradigm.

This is similar to how people are thinking with web services...taken to an extreme. There are already web apps that do their image manipulation, spell checking, or other bits of functionality by sending requests over TCP/IP to a web server and getting XML back. Web standards have been one force for untying people from using any particular operating system, and I think this will keep pushing on that. But you don't need to invoke a network--and I think the most common case will be VM components that are run on the local machine as active libraries with access to the WAN disabled...or updated in a strictly monitored way.

Further thoughts

These ideas push away from goals that we consider important today, like user interface consistency standards. We could have "Night of the Living Dead Operating Systems", where a virtual machine running BeOS on the front end uses an OS/2 codebase to do its computational work, and packages it all up as if it were a "normal" application. This sounds really scary to some people--am I actually advocating this?

Well I'm not even saying that this is the way I think development should be done (besides the part about not wasting effort porting things!). One engineer I talked to sheepishly admitted he'd used a whole chip where basically a flip-flop would have sufficed... but it was easier to plug the part in, especially since he couldn't predict what he might want that subsystem to do later. Similarly, with VMs, I think this convenience of using hardened elaborate components is going to pop up in all kinds of places we'd use two or three lines of carefully chosen code today.