Somehow I made it up to 2007 without ever writing code that opened a raw network connection or pulled apart a TCP/IP packet. Naturally, I had some hand-wavy notions of more-or-less what was going on under the hood--in college I took a 400 level CS course based on an old edition of Tanenbaum's excellent Introduction to Computer Networks. But our homework was all theoretical, and I didn't delve very deeply into the practicality of what powers our modern Internet.

But this year I was tasked to port some Windows networking code to Linux and OS/X. Looking at what was there, I guessed it was no big deal and said I'd do it. After all...there is a layer of abstraction known as "Berkeley sockets" which is practically identical to the UNIX API for reading and writing files. How hard could it be to recompile that on a new platform?

Though sometimes it might not be that hard, this case turned out to include the functionality of a DHCP server. The Windows version was able to work at the socket level by broadcasting UDP packets to 255.255.255.255, but the OS/X and Linux versions fundamentally couldn't do it this way. Their semantics are different for how the socket calls are translated into packets.

I want to talk about some of the high-level gotchas to watch out for if you've just never run up against these particular dark alleys. Because I'm talking about "weirdness" only, I'm not going to explain basic mundane socket programming--because there are many guides explaining that. (One of the best I found was Beej's Guide to Network Programming--so check that out if you're interested.)

How IP addresses are doled out

Most everyone has a basic idea what an IP (version 4) address looks like. The whole amazing story of the Internet is all the wacky mechanics to get a message from the computer that identifies itself as A.B.C.D to another machine that identifies itself as W.X.Y.Z, taking evolving paths. This is where companies like Cisco make their money. I'll skip over the exciting topic of how traffic is routed and talk about the much more bone-headed idea of how addresses are allocated in the first place.

Let's just quickly go to the command line and see what the IP address is for google.com if I ping them:

PING google.com (72.14.207.99): 56 data bytes 64 bytes from 72.14.207.99: icmp_seq=0 ttl=234 time=85.093 ms 64 bytes from 72.14.207.99: icmp_seq=1 ttl=234 time=85.008 ms 64 bytes from 72.14.207.99: icmp_seq=2 ttl=234 time=80.797 ms ^^C --- google.com ping statistics --- 3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet loss round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 80.797/83.633/85.093/2.005 ms

We see that somehow the textual name google.com was converted into 72.14.207.99. Once we get a number, that's when the routing optimization magic starts kicking in. But you might be thinking: "There's a control panel where I can set my IP address to be any number I want. What's to stop me from picking that number, and suddenly intercepting the traffic people intended to send to Google.com?"

At an abstract level, nothing is stopping you from doing this. On your own isolated network (where you control the routing) you can do just that. But your ISP is providing your connectivity to the greater world, and is thus responsible for limiting the nature of your incoming/outgoing traffic. If they assign a number to you like A.B.C.12, you might be able to get away with lying and saying you were A.B.C.13--but the farther outside your "block" you try, the more likely a high-level router in the Internet is going to ignore you.

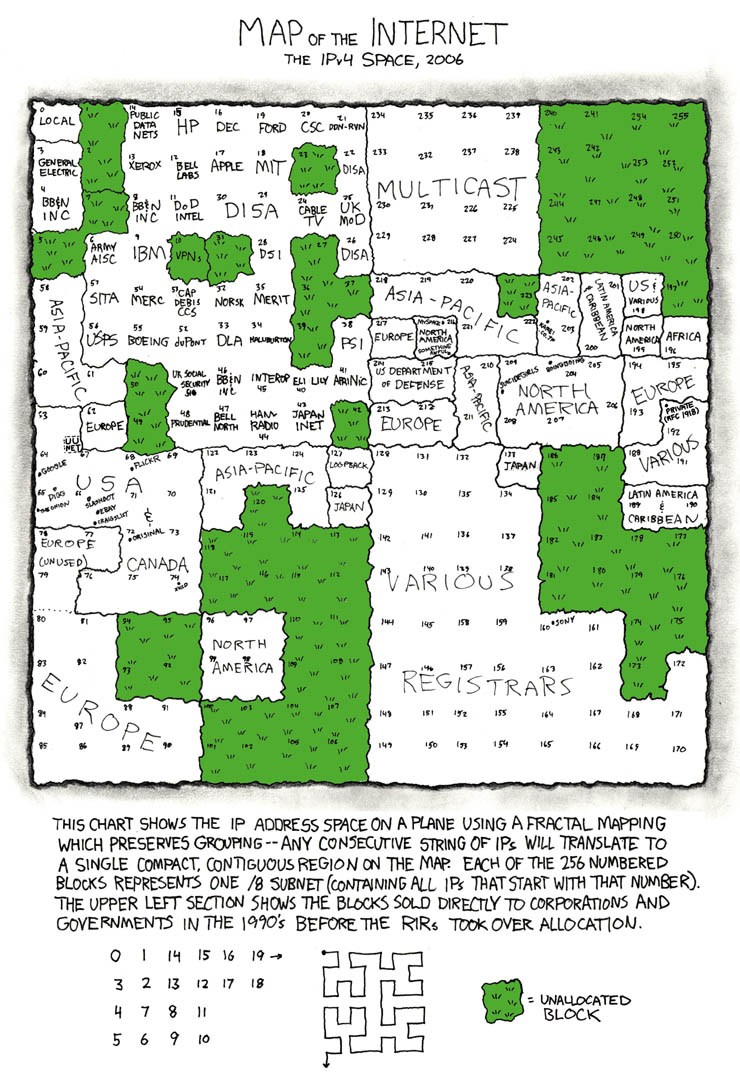

"Officially" recognized IP addresses have been divvied up in a ridiculous process that roughly parallels the Oklahoma Land Rush. One cartoon version breaking it down was featured on XKCD:

If you dig down into this map you'll notice that 72.14.207.99 is assigned to an organization called ARIN. ARIN in turn has given their seal of approval that this number belongs to Google Inc.. Because ARIN is considered a legitimate authority by the average ISP, few routers would ever forward a packet intended for 72.14.207.99 from one of their customers to anyone other than Google.

Note

Hackers are constantly trying to subvert this, of course. Though I'll point out that since who-gets-what-number is based more on money and cybersquatting than it is on actual legitimacy, it's not like you should have all that much faith in the powers-that-be. In the words of the X-files: Trust No One--and that includes your ISP...especially if it's Comcast!)

When reading socket sample code, you often find two routines for finding machines on the net. One is known as

gethostbyname and the other is gethostbyaddr. You might expect that if you have a number that works from the command line in ping for finding a machine, that gethostbyaddr would work for that address as well...but this is not necessarily so.

The reason is that just because something has an IP address doesn't mean it has a host record with your domain name server. If you feel like bypassing the DNS, you might still be able to open a socket connection to it via a directly coded

sockaddr_in (as ping does). But by doing so, you better know what you're doing...because you're bypassing any checking that your DNS servers might have been doing to make sure that IP address is who they are claiming to be!Dynamic IP Addresses

We know there's such a thing as a "static IP address" where you tell the machine what address has been assigned to it on the Internet map. There's another thing known as a "dynamic IP address"...where each time you connect your computer a server tells it what address to use for that session. If you turn your computer off you lose it and have to get it again, and it might be different.

Just because an IP address is dynamic doesn't mean it gets to ignore the rules of the Internet allocation strategy. If you want to talk to other computers, then the dynamic address must fit into the map. But what if you're setting up a local network of thousands of computers and you don't want to interfere with the rest of the world? Are any addresses reserved that are not meaningful on the global internet, but you can use locally and not be considered a liar?

Well, there were, and you run into them rather often...such as these private network ranges:

- 10.0.0.0 -- 10.255.255.255

- 172.16.0.0 -- 172.31.255.255

- 192.168.0.0 -- 192.168.255.255

So let's say you were Google and you own thousands of machines, but the only address you have registered through ARIN is 72.14.207.99. You can use that address as a bridge for connecting to the broader Internet, while your corporate machines all have private addresses to talk to each other. It's kind of like when people inside a company are using extension #s off of a main line instead of having their own full telephone number. All traffic intended to come in and out of the global internet will go through the main number and then be forwarded to the right local address.

If you're the average internet user, chances are that you have a private network address right now. You're probably connected over Wi-Fi or a router that lets you share an Internet connection with the public internet number handed out by an ISP. For instance, on my machine right now connected via Wi-Fi I am 192.168.1.3:

bash> ifconfig

...

en1: flags=8863<UP,BROADCAST,SMART,RUNNING,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1500

inet 192.168.1.3 netmask 0xffffff00 broadcast 192.168.1.255

ether xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx

media: autoselect status: active

supported media: autoselect

(...)

But if I go to http://www.whatismyip.com/, it reports a public number belonging to my ISP.

If you are enjoying the study of these magic numbers and how they are handed out, you might be interested to know that a poor technical decision led to the loss of all the 127.xxx.xxx.xxx numbers save one--127.0.0.1. This is an alias for your own machine, known as Loopback. Wikipedia's article on the topic explains how a similar oversight in inconsistent implementations led 0.0.0.0 to be unused.

The DHCP Protocol

So let's say your machine gets a dynamic address from whatever router or coffee shop you happen to wander into. How does your machine find out what number it's supposed to use? There is a chicken-and-egg problem: the server that hands out addresses can't tell you who you are with a message addressed from itself (A.B.C.D) to you (W.X.Y.Z), since you do not yet recognize that traffic for W.X.Y.Z is meant for your machine!

Special IP address formats, such as 255.255.255.255, were reserved to mean "send this message to everyone on the network, whether they have an assigned IP address yet or not". So a machine looking for an IP address would thus broadcast a magic number to 255.255.255.255 and say "if anyone listening on my network would like to give me an IP address, then please broadcast back to 255.255.255.255 the magic non-IP-address number I just sent (so I know you're talking to me), along with the IP address I should use."

You might be guessing that the semantics of these "special" addresses are going to be a little wonky. In other words, don't expect to telnet to 255.255.255.255 and have anything interesting happen, such as simultaneously connecting to every computer in the world:

bash> telnet 255.255.255.255 Trying 255.255.255.255... telnet: connect to address 255.255.255.255: Permission denied telnet: Unable to connect to remote host

Given the fact that you clearly can't use these magic addresses anywhere you might put an ordinary IP address, then when can you use them? And since you don't expect all the millions of computers worldwide to get your message... which subset of computers will actually get it?

Remember how when you try to send a message pretending to be Google's IP address and it gets squashed once you bubble that up toward the Greater Internet? Any messages you broadcast to 255.255.255.255 will be squashed at least by then, maybe sooner. The lost messages can even happen inside your computer, such as one with multiple network cards--the socket layer might send the outgoing data to only one of the cards, or to neither!

So if you are reading socket code and see any IP addresses with 255's in them, start worrying. The broadcasting phenomenon is handled differently on various platforms. You might get the desired behavior on one platform or when only one network card is plugged in, but to get the behavior you want you might have to use a lower level API than the socket layer.

Going underneath the socket layer

Socket tutorials on the web give the surface impression of being everything you need...and certainly they're adequate for a lot of basic programs. But the coolest network apps and utilities need more. The code inside of a router itself is probably not done with sockets, Skype is basically hacking and shaping on the packets themselves with their application--that's how they work magic.

Some great exploratory network tools are based on simple socket layer, such as netcat. But if you're in a case where you need to go deeper, such as what I found with DHCP, you need something more powerful.

Where to start? One good place is libpcap for receiving packets off of specific network cards in your machine (including the ability to do "hackerish" things like read packets not intended for your address). This is the foundation of the more powerful tool known as tcpdump.

Especially important for cross-platform network code dealing with packets is the libnet library. Not only does it have some APIs that make it a little less tedious to build various packet types (e.g. by implementing checksums for you), it can find out the hardware Ethernet address of an adapter in a cross-platform fashion. Plus, it has defined structures for every networking struct you can imagine!

Note

The libnet project's homepage is a little out of date. Refer to the updated documentation inside the archive.)

Special thanks

I'd like to thank Peter Sichel from the Apple Network Programming mailing list, who was very helpful while I was dealing with the DHCP porting issue. He makes a product called IpNetRouter for OS/X. Here's our conversation thread: