Not many people have the ability to look at the few fundamental elements of a system (such as constructs of a new computer language) and extrapolate the long-term implications of their use. But rather than jump in and tackle the difficult question of understanding the expressive power and limits of computation, I'll start by talking about a simpler problem. Don't panic: it involves crayons and coloring!

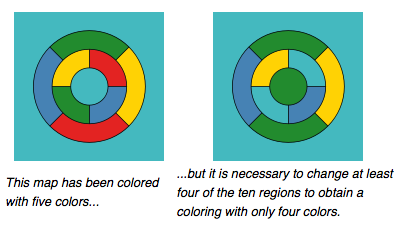

This example is going to seem pretty easy on the surface, and you may be familiar with it already. It involves trying to find a way to color in maps so that no areas which share a border are going to be the same color. Here's an example of a simple coloring with 5 crayons, and then finding a method for doing it with only 4, taken from Wikipedia's article on the subject:

Without prior knowledge, the average Joe can only guess at how many crayons he'd need to reliably fill in any map he is given. Just by trying a few cases, he might get an intuition that a small box of different colors will do the trick. But if Joe knew the Devil was going to be presenting him with an arbitrary map and getting his soul if he couldn't color it properly, he'd probably buy Crayola's biggest box...120 colors! (Plus, because he doesn't know for sure that even THAT would be enough, he'd also probably try to round up the discontinued colors off of eBay!)

Yet there is salvation from this kind of paranoia. Early formalisms of the map-coloring-problem from mathematicians comforted us with proof that it never took more than 5 different colors...and that 3 will certainly not always be enough. After considerable debate and experimentation over the years, we ultimately found that we only need four unique colors for any map the Devil--or anyone else--makes.

Note

Depending on your purposes, discovering it was 4 vs. 5 might be somewhat academic. I myself feel that the more crucial step was bringing in math to save us from needing to pack a potentially infinite number of crayons.

Now...what if the "Devil's Map" you must solve is instead an arbitrary selection from mankind's constant creation of new ideas for software? That raises a lot of questions about what a programmer needs in their backpack to be confident they could correctly "color in" any program specification with a working implementation.

Programming analogue to the map coloring problem

The following questions are not going to boggle the mind of an experienced computer scientist, but they are things that not everyone thinks to ask:

- Does one need to pack a language with, say, multiplication built-in... or should you just add a number to itself repeatedly in a loop?

- If you discover don't actually need multiplication, then doesn't that make the need for addition and loops seem suspicious?

- Is there anything that computers could never solve efficiently? (Or if that ever happens, is it just the case of the programmer just "missing a crayon" that the language designer accidentally forgot to put in his backpack?)

These are the kinds of great conundrums that preoccupied early computer scientists. Smart guys like Turing and Church came up with pretty deep answers. These folks were busy defining mathematical abstractions of computers and "computer languages" that were extraordinary simple, but could do anything that any other generic computer could do. I think Turing's own words on this subject are surprisingly easy for the layman (and better than many textbook rehashes).

But trying to program in a Turing Machine would be somewhat analogous to facing the Devil's Map-Coloring Challenge with 4 crayons that had been put through a Cuisinart! You can have complete confidence that your bag of gray-looking dust will let you color in areas just as you could with four whole crayons. But you'll have to spend an unreasonable amount of time sifting the particles and sorting it into piles with your hands, then rubbing it into the shapes with your fingers. On top of that difficulty, you might find that Beelzebub picked a map that's really hard to color with just 4--sometimes the 4-color solution takes a lot of time to find!

The fact that someone theoretically could find a way to overcome these obstacles doesn't mean you'll have the patience. So if crayons are cheap, you might want to pack the 120 color box anyway...even if it's overkill. At least that way, any map with 120 states or fewer will be easy to color: pick out a crayon, color a region, and just don't use that one again!

Now, a more slippery issue...

In the previous sections I discussed somewhat mathematically precise questions. But what if the challenge was a bit more abstract? Let's say the Devil was going to ask you to produce a work with actual artistic merit for any given thing he might ask you to draw--be that a landscape, or a space battle, or a unicorn. How many crayons would you need to make sure you could meet his challenge?

I don't think there'd be much controversy among artists in saying that this has very little to do with how many colors you are given. Subtle differences arise in works by those who had green crayons vs. those who only had blue and yellow in their set. But it's still "crayon art", and most critics believe that that anyone with talent should use something different (like oil paint).

Arguments about medium can become very passionate. Still, people agree that it is useful to speak of Crayons and Oil Paint and LEGOs as being markedly different...despite some similarities in how a creative mind might apply them. Yet few would suggest that a box with more or fewer crayons should be labeled a "new" medium.

Programming is the "math problem" AND the "art problem"

I chose to start with map coloring because it's a rigorous problem-solving domain with artistic overtones. That's because I wanted to bring up the idea that when you are given a programming challenge, doing the work well is not just solving math equations as some people think. Those immersed in the field start to see it more as being commissioned to make a work of art. And every artist has a medium they enjoy working in (sometimes to the exclusion of others)!

Lisp and C++ are considered different mediums by most everyone. A programmer needs to use a different state of mind to program in them entirely, and that gives rise to different program types. Yet C++ and Java are very similar in their overall nature with only a few strategic decisions made to differentiate the languages.

What does it mean for a language to be a truly new medium, as opposed to a variation on a theme? That's rather debatable. A language I have been looking at lately is called Rebol, and its advocates believe it to be a unique new medium. This is despite the fact that on first glance, it is an incredibly small box of crayons with a special color or two added, and lots of "ugly" colors taken out.

Yet to them it's also not like any other language that already exists. So if it were a product being introduced at Toys R Us, it wouldn't be a LEGO set with square plug-knobs instead of round ones....nor would it be finger paint that was merely a little stickier or a little easier to clean up. Beyond it's new-ness, its champions say it also has the property of good-ness: a hopeful new way to build fun art.

Bold claims! But I've become interested in the way Rebol has simplified the language and interpreter so that it yields a somewhat homogenous computing substrate. It's hands-on, and doesn't have properties that will suddenly surprise you as you dig in. I will post another article on Rebol and its benefits soon, and link to it from here.

Addendum: note on inspiration for this article

The phrasing in this article was motivated by a quote I read: