This is the third of several articles I'm going to write about the Rebol programming language. To learn more about it, you can visit rebol.com. But my hope is to demystify some of its strengths and weaknesses in a way that their website currently does not, so if you read what I write first then it might help. :)

UPDATE

Rebol version 3 is now open source under the Apache 2.0 license, so all those disclaimers I used to have in my Rebol articles about not getting attached to a proprietary language are no longer applicable! Use it without hesitation!!!

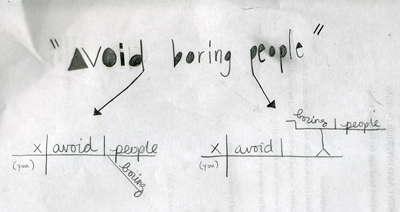

We know from the English language that humans are a bit lazy when it comes to expression. We're always dropping syllables off of words if we use them often, or taking difficult combinations of letters and turning them into something easier to pronounce. Yet of course, this means we live in an environment ripe for ambiguity, as in this graphic by Deena Hyatt:

By contrast, computer languages typically make programmers be redundantly clear in their notations. You're always dealing with syntax... putting in parentheses before a list of arguments to a function, putting a close parentheses to say when you're done. There are semicolons in many languages to tell the computer when you finished a line.

Yet we get a lot done with English without that symbol soup. Somehow, we communicate to each other with little more than a series of words separated by spaces. Essentially, that's what a Rebol program is... "words" separated by "spaces". It has conspicuously few parentheses or semicolons. Or equals signs, for that matter! If you strip out some of the incidental uses of symbols in names, it might be mistaken for human writing.

Note

Some of the stranger notational aspects are just for show, for instance the function named none? could have just as easily been called isvaluenone... you can change it to that if you want to. But the question mark convention is nice for boolean functions.

So keep that interesting aspect in the back of your mind while I go straight for the jugular in terms of things about Rebol that may seem totally insane. I'm just being up front and honest with you about things you will find surprising. I will talk about the curious upsides after we've banged our heads against our keyboards a few times.

Whitespace matters in Rebol, a lot

I mentioned that Rebol programs are basically words separated by spaces. The text "hand book" and "handbook" have unique meanings in English. When not inside a quoted string, spaces indicate full stops between most all tokens. So there is a difference between

1 + 2, 1+ 2, and 1+2 in Rebol:>> 1 + 2

== 3

>> 1+ 2

** Syntax Error: Invalid integer -- 1+

** Near: (line 1) 1+ 2

>> 1+2

** Syntax Error: Invalid integer -- 1+2

** Near: (line 1) 1+2

The first is a series of three items... and has the effect you probably meant. The second as a series of two items (

1+ and 2). The final we might hypothetically think of as a single token called 1+2. Now...as perverse as this sounds...you can give each of these cases different meanings. Please don't panic as I show you how to make 1+ an alias for the print command.Note

We have to use an API to build such a program, because if we went through the default parser with a token like

1+ we'd get a syntax error. Yet this has nothing to do with Rebol's runtime, which is quite agnostic about names.

First let's make our crazy program:

>> crazy_program: reduce [(to-word "1+") "Hello world"]

== [1+ "Hello world"]

The first symbol in this series isn't a string, it's what Rebol calls a

word!. Now we will make the word! an alias for print. Once again we have to write it in an odd way to keep the parser from choking:>> crazy_assignment: append reduce [(to-set-word "1+")] [:print]

== [1+: :print]

Now that we've got our new definition for

1+ and our crazy program that uses it, we can run the evaluator on them to see our totally loony result:>> do crazy_assignment

>> do crazy_program

"Hello world"

UPDATE

This works in Rebol 2. But the ability to use programmatic methods to create "weird words" starting with digits, or that have angle brackets or spaces in them, was removed in Rebol 3. A final decision on prohibitions of this kind are still in the outstanding design issues pool.

I bring this aspect up now to make the point that spaces matter in day-to-day Rebol programming... a lot. One of the few places you don't really have to worry about them is near brackets and parentheses, so these three things are equivalent:

>> first [print "Hello world"]

== print

>> first [print "Hello world"]

== print

>> first [ print "Hello world" ]

== print

Yet there's an oddity in the console when it comes to newlines. If you tried running the following:

>> first

[

print

"Hello world"

]

You'll get a weird error:

** Script Error: first expected series argument of type:

** series pair event money date object port time tuple any-function library struct ...

** Near: first

>> [

[ print

[ "Hello world"

[ ]

== [

print

"Hello world"

]

Because there was a newline, the "first" command thought you were missing an argument. The following code would work as expected, because the bracket which starts the series parameter is on the same line as the command:

>> first [

print "Hello World"

]

== print

This particular issue only happens if you are running at the command line--not if you are running a script from a file. But generally, Rebol programmers abide by the convention of not entering newlines in a statement unless there is an open brace. So the

either function (which is equivalent to an If-Then-Else, and hence takes three arguments) would generally be written as:>> rebol-is-very...interesting?: true

== true

>> either (rebol-is-very...interesting? = true) [

print "Is Rebol very interesting?"

print "Signs point to yes"

] [

print "Is Rebol very interesting?"

print "My sources say no"

]

This will print out:

Is Rebol very interesting? Signs point to yes

Notice the free usage of hyphens, periods, and question marks in tokens... something that you aren't allowed in other languages.

Non-Scalar Literals Must Be Copied Manually

The following Rebol program looks fairly straightforward:

>> myBlock: []

>> append myBlock "A"

>> append myBlock "A"

>> append myBlock "A"

>> probe myBlock

["A" "A" "A"]

>> append (first myBlock) #"B"

>> probe myBlock

["AB" "A" "A"]

It makes a block, puts three "A" strings into it, then adds the letter "B" to the first element. Simple...BUT...you'd get a very different result if you had used a loop to do the initialization:

>> myBlock: []

>> loop 3 [append myBlock "A"]

>> probe myBlock

["A" "A" "A"]

>> append (first myBlock) #"B"

>> probe myBlock

["AB" "AB" "AB"]

This is because in the first example, there are 3 different "A" strings declared in the source code. In the second, there is only one "A" string...referred to three times. If you actually want three copies, you have to duplicate that source-level string by using the

copy command:>> myBlock: []

>> loop 3 [append myBlock (copy "A")]

>> probe myBlock

["A" "A" "A"]

>> append (first myBlock) #"B"

>> probe myBlock

["AB" "A" "A"]

This won't shock C programmers too much. They're used to having to make copies of literal strings if they intend to modify them at all. But it's a bit surprising when compared with other common interpreted languages, and a source of frequent misunderstandings. Especially since it applies not only to string literals, but also to block literals:

>> myBlock: []

>> loop 3 [append/only myBlock [A]]

>> probe myBlock

[[A] [A] [A]]

>> append (first myBlock) 'B

>> probe myBlock

[[A B] [A B] [A B]]

Note

People typically wish

append [A B] [C D] to produce [A B C D] and not [A B [C D]]. Yet the latter is the more "natural" definition of appending in a programming sense--so there is special code which makes the more common option the default. Above, you see that I am using the /only refinement...which in this case can be roughly interpreted as "only do the raw append, don't run the extra code which protects you from the uncommon case of nested blocks".

Rebol has erred on the side of efficiency by avoiding copies in cases where they might not be needed. This only applies to Rebol Series (REBSER)--not Rebol Values (REBVAL) such as integers or dates, so you don't have to worry about copying those!

Highly permissive evaluator

One property of Rebol is that when a block is evaluated, the "value" is always whatever the result of the last expression in the block is. This is also a convention in languages like Ruby, whose functions evaluate to the last expression in the function's code. So if you said:

>> 1 + 1 2 + 2 3 + 3

== 6

A frightening implication of this is that there's nothing checking to ensure you didn't pass too many arguments to a function. For instance, I've been using print in these examples, and it only takes one argument--the object to print, and it returns nothing at all. If you pass more values to it... guess what happens:

>> print "Goodbye" "cruel" "world"

Goodbye

== "world"

Let's break down what happened here:

printtook its one argument, and once it was fulfilled, it knew it could run...so it did, and printed "Goodbye"- Next in the left-to-right evaluation was "cruel", and it was just a string constant with no side effects so it vanished into the void

- Chugging merrily along, the interpreter saw "world" also evaluated to a string, but had the peculiar property that it was the last item in the series... so the overall expression has the value "world".

In C++ this would have been:

std::string MysteriousPrint(

std::string printMe,

std::string ignoreMe,

std::string returnMe)

{

cout << printMe;

return returnMe;

}

MysteriousPrint("Goodbye", "cruel", "world");

This can feel a whole lot like walking a tightrope without a safety net. It leads to some puzzling errors... that are especially puzzling to new Rebol programmers. Yet it does mean you have a rather interesting pipeline of processing on every line of code.

There's no operator precedence

Look at this little snippet of Rebol code, which does what you'd think:

>> add 1 2

== 3

Similarly, there is multiplication:

>> multiply 2 3

== 6

Despite the existence of these verbose keywords, Rebol lets you represent these as seemingly infix programs:

>> 1 + 2

== 3

>> 2 * 3

== 6

DO NOT be fooled by this. That's just a shorthand, and under the hood it's still a left-to-right expression evaluator. For instance, check this out:

>> 1 + 2 * 3

== 9

Yowza. You have to use parentheses if you want to get the expected result:

>> 1 + ( 2 * 3 )

== 7

Further adding to the weirdness, the parentheses are first-class objects within the interpreter. Like blocks, they are part of the abstract structure. You can even make a series of parentheses:

>> first [ ( ) ( ) ( ) ]

== ()

This means every time you use parentheses to disambiguate your code, you are making the program bigger and slower to evaluate. Also, there are some pieces of Rebol that use parentheses for things other than precedence. (For instance, the

compose function will search a block for parenthesized expressions and evaluate them, leaving any code that isn't in parentheses intact as literal code.)

So if you show a Rebol developer any code with parentheses, they'll encourage you to take as many of them out as you can. That's going to grate on some people who build formal systems and don't want to be "taking out parentheses in order to Rebolize the code".

You're kidding. How can I code under these conditions?

I really think that to understand why one might use a language with these properties you have to take a serious look at what makes us use English. Why do we like writing a bunch of words in a line and then ending it with a period, instead of something more "formal"? I'm not sure, but I do suspect that if English required you to call out the noun phrases or subclauses in a sentence, then...

<< [ ( people ) | would probably ( use ) >> | { something , else } ] !

Every good language makes you think differently. In fact, one of my favorite free C++ books online is titled Thinking in C++. Yet Rebol tries to not stray too far from our natural instincts for language just to appease a computer's thirst for formalism. Instead it encourages fluidity, and fulfills the confusing promise of "no reserved keywords"... as in English, everything can be overridden or given new meaning.

It takes some getting used to, certainly. There is no need to look further into the language if you could not (under any circumstances) work this way. But if you think that you'd be willing to accept these ideas if there was a payoff like the one I described in Is Rebol Actually a Revolution... then you should check out my next articles!