Michael Hartl is spearheading a campaign for a cause that is near and dear to my heart. He wants to fix the fact that we are living with a suboptimal choice for the value of π:

About a year ago I did a hunt on the web to see if anyone besides me had campaigned for changing the value of the fundamental circular constant we use to 2π. At that time, I only found the essay Michael cites: "π is wrong" by Bob Palais, which was published in 2001:

Bob notes that the reactions he got ranged from "obviously" to "you're nuts". I'm personally in the "obviously" camp. Especially because in 1995 I gave an informal talk at my university called Clocks that Run Backwards (and other Innovations). In it, I suggested several foundational changes which would eliminate "accidental complexity" that I felt was burdening early education. Changing the circular constant was one of my big pushes.

I am almost 100% certain that other Quixotic-types must have espoused the idea before I ever thought of it. But I seem to be the earliest we know about (so far) who was crazy enough to treat it like an important topic in public--while sober, even.

UPDATE

The rising popularity of tau has gotten another proponent of "pi is wrong"--Joseph Lindenberg--to come forward with a 1991 paper he wrote on the subject. Some of the ideas I had in my talk were things I'd cared about long before, such as the issues about fixing clocks. But it was specifically doing EE homework that inspired my annoyance with the chosen value of pi--so I probably only started talking about it around 1994. Anyway....

Though no recording exists of my presentation, I can call witnesses. In fact, one guy who came to the talk wrote my argument in response to a math question on an exam he didn't know the answer to. He argued that he didn't have to answer it due to religious objections to the choice of the value of pi. I think the TA gave him 0.628 points for the answer.

Note

On another question on that test for which this fellow did not prepare, he wrote "6 * O, where O is defined to be 1/6 of the answer to question 21"--or something to that effect. I don't want any of the blame for that idea, though!

Michael and Bob (and Joseph) have made the arguments, and expanded upon them with more formal justification than I ever have. So rather than repeat that here, I'll lay out how my proposal differed...as well as a few other things I talked about.

Naming

I didn't call the constant turn or tau. Mine was the "cycle", which reveals my electrical engineering bias!

When I was exposed to "turn" last year, I thought it was clever and probably better. But Michael makes some good arguments for avoiding something that sounds like an English word we'd want to pluralize/etc. Were I sticking with this proposal today I might suggest only using "cycle" in very early education, and then later encourage shortening it to "cyc".

Note

There may be a similar compromise for tau...to start with calling the constant "turn" and gradually shift it to "tau" after comfort is established.

Symbol

These two other proposals have chosen to go with something of a pun on the pi symbol. Michael's approach in cutting off a leg could be seen as "remove a dividing ratio to the true circular constant". (One leg means 1:1, two legs means 1:2?) Adding another leg to pi is kind of clever as well--it's as if doubling its width would double its value!

While I admire their efforts to bridge compatibility with the existing symbolism, it raises an important question. If you're going to bow so deeply to pi's influence, why not just call your symbol "2π"? Then just teach people not to involve the 2 in the surrounding math, and you're done.

Note

This obvious compromise is what tau-ists and turn-styles do when they have to work with the pi-ous. Just leave your answer looking like "3/7 * 2π3" instead of doing the obfuscating expansion of "24/7 * π3".

So I wanted a full break from tradition. My symbol would be foundational in terms of semiotics (even though I didn't learn that word until years later). I wanted the constant to look "circular" somehow, and didn't care if it could be related to pi at all!

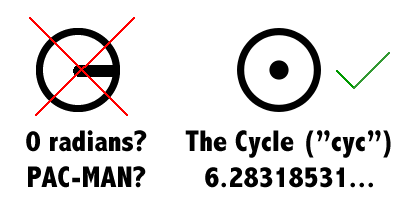

I'd been carrying around this idea in my head that it would look like a broken theta, showing a radius connecting from the center to the rightmost point. But at the last minute before my talk I'd changed it to a circle with a dot in the middle, because I felt that communicated "the whole cycle" and seemed less like "zero radians" (or "pac-man" :P)

Some places claim circle-dot is claimed by the direct product operator, but it doesn't show up in the Wikipedia article for direct product. So I'd prefer to reclaim it for the circular unit. The circle-dot-symbol options in unicode (⊙, ◉) aren't stellar in many standard fonts, but I'll point out that pi and tau aren't always so good either...

One concern I have about tau is that in equations involving "τ" and "t" for time it might cause confusion. Just imagine looking at pendulum equations, or signal processing in the time domain. The second leg on pi really differentiates it from our existing letters.

Mathematical Arguments

Bob and Michael (and Joseph) have said plenty. In my own case, I leaned a little more toward "it's obvious" from all the examples where 2π was appearing. I could point to these in physics and EE books.

But the people who our new circular unit would help most would be those trying to learn from scratch. So people asked me if the formulas one encounters early on for circles were getting easier or harder. The formula for circumference of a circle looked "simpler" after the change, but the formula for its area looked "more complicated":

- Circumference: 2πr vs ⊙r

- Area: πr2 vs 1/2 ⊙r2

This was the most frequent question I've gotten. But my response was essentially the same as Michael's. Namely the appearance of the "1/2" may be masked out by a haphazardly doubled constant in this case. Yet there are many other relationships that come from integrals and derivatives that don't involve any foundational constants.

Think about the momentum and kinetic energy: [mv => 1/2 mv2]. To get rid of the halving in the kinetic energy equation you'd have to start measuring things in "double-masses", which would be ludicrous and only push the 1/2 into the momentum formula.

So that 1/2 belongs in the area of a circle. And it's a cognitive time-bomb to have it missing!

Clocks that Run Backwards

Time telling is a naturally cyclical process. That's not surprising, since the days we measure relate to the full rotation of our roughly-spherical Earth! The visceral way in which we experience one day to another makes it a perfect place to lay our foundations for studying radians in math.

But the exact same mistake was made with analog clocks as was made with pi! The big hand makes a full sweep around the clock and yet only half a day has passed. Seeing the relationship between these two failures, I argued that children learning to tell time should have access to a saner analog clock. It would convey a whole day in one sweep.

Because the clocks would have to be re-manufactured anyway, I decided they should be consistent with the existing (arbitrary) mathematical conventions for radians. The big hand would point right at midnight, and cycle around "counter-clockwise" until it returned there on midnight the next day.

I wasn't terribly interested in analog clocks with more than one hand...rather the idea that a marker could be put on the edge by parents to indicate times of events. The point was to build comfort with cycles and thinking in terms of them, and to have that intuition easily map into math.

"Metric Time"

Not knowing that the term "metric time" was being used already for something else, I wanted to couple this with the idea of switching from 24-hour time to 25-hour time. These 25 divisions would be around the edges of the analog clock.

Each "hour" would be 2.4 minutes shorter. Each "half hour" would be 1.2 minutes shorter. Each "quarter hour" would be 0.6 minutes shorter. My argument was that this would not greatly impact the usefulness of any of these traditionally useful divisions of time.

Once a day has 25 hours, a digital watch with only 2 digits can meter out roughly every "quarter hour". So for example:

- .00 - midnight

- .04 - an "hour" after midnight

- .50 - noon

- .52 - a "half hour" after noon

etc. And a 4-digit display could get a resolution of about 8 seconds:

(24 * 60 * 60) / 10000 = 8.64

One could say "it's 99 o'clock" if one wanted to to convey 0.99; and one could of course use notations like 40:50 to represent 0.4050. Obviously a nice thing about this is how it deals with math on times, because you can carry and borrow out days.

Swatch Tries a Variant

It's another idea that must have been in the collective conscious somewhere. Because Swatch released "Beat Time" two years later, in 1998:

Someone who knew about my campaign to change time bought me one of the watches for Christmas. A nice thought, but it was hideous. I carried it around in my suitcase to use as a travel alarm clock...never in beat time mode:

They eliminated time zones because their marketing wanted to create a "global time standard", since the Internet was connecting people simultaneously across the globe. They picked the headquarters of Swatch as the timezone for midnight. They also focused on the 3-digit format rather than thinking of it as something you'd teach as expandable to however many digits you needed.

Those all were kind of against my premises. I was really thinking about the "daily cycle"; on another planet where it turned faster or slower you'd adapt it and the meaning would change. There'd be another layer of "atomic clock time" which would be used for synchronizing the universe... but this would just be a calculated from that... the way our computers adjust UTC times for our zone.

Other Stuff

Some of the other things I talked about were my ideas on restructuring education so it took children through more of a guided development, rather than dropping the final answers on their lap first. This would mean teaching hash marks first, then roman numerals, and let kids grasp the pitfalls of simple systems in order to motivate them to appreciate more complicated ones. When they were ready, then introduce place value and decimal/binary.

Historically we've been afraid of this because school prepares people for society. It's too risky to have dropouts who haven't gotten to the part where they learned decimal numbers. There won't be a translation of prices on food at the supermarket into Roman Numerals! My argument was that pocket computers are going to change this and we really have to emphasize understanding.

Since this time people have told me that some of these ideas are aligned with the Montessori method, though I have not studied their programs in depth.

I also made arguments about how games which taught by the nature of the rules of play were ideal. Trivial Pursuit, while a fun game for (some) adults, is an example of the format I did not like. Essentially any "game" where kids essentially have to answer a flash card and then that dictates whether they move on some unrelated board. Much better were things like Battleship, which could teach a coordinate system as a natural part of play.

Note

I still wonder why there isn't Battleship for spherical coordinates, cylindrical coordinates, etc.